KLDE

The Klde settlement is situated on a terraced slope at the confluence of the Mtkvari and Potskhovai Rivers near the Turkish border in southwestern Georgia, along a major trade route that once linked the South Caucasus and eastern Anatolia. The site, encompassing a large multi-layer settlement and a cemetery, extends over 3,486 square meters and includes structures, graves, and storage pits. The excavations yielded excellent and extensive cultural material from the first millennium AD. The settlement appears to have been destroyed by fire and rebuilt several times. The last fire in the 7th century AD, possibly during the campaign of Byzantine Emperor Flavius Heraclius or during an Arab invasion, led to the abandonment of the site. The structures excavated during the pipeline project appear to have been domestic and were constructed from stone with tile roofs. All the dwellings possessed hearths for cooking, generally located either in the center or corner of the structure. The settlement’s layout leads archaeologists to believe that the structures also had a defensive purpose. Several stone sling bullets of different shapes and sizes may have been a means of defense against attackers.

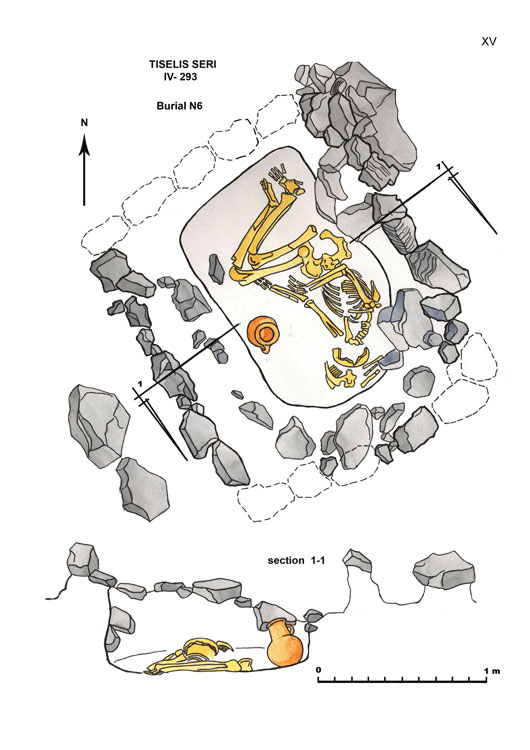

Interment at some of the burial sites at Klde, which were concentrated in three separate areas, occurred in stone-lined pit graves, some of them edged with stone, while others were in wine jars. Many of the skeletons were lying on their backs, but others were on their sides in crouched positions. These differences mean the burials took place in at least three cultural periods and may reflect broad religious and other cultural changes overtime. Indeed, in the region under the Kartli (Iberia) Kingdom, differences between pre-Christian and Christian funerary cultures shed light on the shift to Christianity, with some graves manifesting both Christian and pre-Christian funerary traditions.

A particularly interesting find at the Klde site, dating to the 3rd-4th centuries AD, is a platform that contained 15 ritual vessels along with human bones. However, a clay altar in a corner suggests that the site was a place of cult worship rather than a burial site. The altar bears both Roman and Persian reliefs. The right hand of one figure is raised in a way similar to a gesture of adoration of kings and gods found in the Parthian artistic tradition. Burned areas on the altar, along with the decorative motifs, suggest traditions associated with Zoroastrian altars.

The site contained other interesting artifacts, such as a Roman lamp and a Parthian silver drachma (coin) of King Gotarzes I. The latter suggests that the Kartli (Iberian) Kingdom was actively involved in Roman-Parthian political and economic relationships connected with the Silk Road. A small fragment of red terracotta with animal figures—some standing, others in flight—was among the finds at this site. Finally, three glass intaglios (made of glass or jewels, with carved decorations) probably date to the second half of the 1st century AD, judging by their shapes and styles. All were similar, suggesting they may have been produced in the same workshop.

Orchosani

The archaeological site near the Orchosani village, located in the Akhaltsikhe region of southern Georgia (historically referred to as Samtskhe),is an excellent example of one of Georgia’s longest continuously inhabited sites. It seems to have been in use since the Lower Palaeolithic Auchelian period. Surface finds include tools made of andesite and basalt (hand axes, scrapers and flakes). Its history spans from at least the Early Bronze Age (perhaps as early as the 4th millennium BC) right up to the early 17th century AD, when the settlement suffered a violent end. Only three structures remain: one from the Bronze Age Kura-Araxes culture, and two from the Medieval Period. Aerial views reveal a large fortified wall around the village dating to the Early Medieval Period.

The 4th-3rd millennium BC was a vibrant time at the Orchosani settlement, which seems to have gone through three distinct cultural phases. The first, that of an early agricultural society, left behind only fragments of pottery, black or grey in color, similar to vessel types discovered at cave settlements in western Georgia. The Kura-Araxes culture came next, around 3,500 BC, with its distinct mud brick homes, elaborately polished black exterior and red interior pottery, and blend of agriculture and pastoralism. Orchosani yielded many artifacts in the Kura-Araxes style, including an anthropomorphic terracotta figurine. Little is known of the third culture to inhabit the site, the Bedeni. Jewelry and other metallic objects from this and earlier periods of the Bronze Age were probably imported from Anatolia, as evidenced bya bronze mattock that with a higher ratio of nickel than is found in Georgia.

Although the Orchosani cemetery produced few artifacts, the surrounding settlement yielded objects spanning many time periods. The most stunning were the large 500-600 liter wine storage jars known as pithoi (a Greek term describing large storage jars of a particular shape) dating to the 12th century AD. Stone, metal, and bone objects that served a variety of purposes, from culinary to military, were also recovered. Religious art from many eras was well-represented in the form of statuettes, inscriptions, and jewelry.

The impressive materials discovered at this site are all the more remarkable considering that Orchosani was completely destroyed twice. The first time was in the 10th century AD, most likely during the Seljuk Turk invasions of Georgia. Orchosani was again destroyed in the 17th century AD during the Ottoman expansion of the area, causing its final demise.

Saphar-kharaba

Archaeologists found more than 100 burial chambers encircled by basalt at the Saphar-Kharaba necropolis in the historic region of Trialeti (Tsalka District) of southern Georgia. Analysis suggests that the site was used in the 15th-mid-14th centuries BC. With only a few exceptions, the rectangular graves were uniform. Each contained skeletons in crouched positions oriented north to south, a pattern that indicates well-established funerary practices. The graves also contained several distinctive artifacts. For example, a cylindrical seal depicting a figure kneeling at an altar with a rod in its hand is a common motif of the Mittani or Hurrian art that was widespread in the Levant and Mesopotamia. Other objects include bronze daggers and surgical scalpels of a type not common elsewhere in the Caucasus.

One of the graves contained a poorly preserved wooden cart with the remains of an axle, wheel, and yoke. Two clay vessels were positioned on what remained of the cart’s bed. Under these vessels, human remains were found. Unfortunately, archaeologists did not discover this grave until after the pipeline construction had disturbed much of the contents, making it difficult to reconstruct this particular burial.

A skeleton of a man believed to have been 40-50-years-old has particular significance because samples of fabric were attached to it that provided clues to the type of fabrics produced in Georgia during this period. The samples were linen, cotton, and wool dyed with pigments that at the time could only have been extracted from mollusks along the Mediterranean coast. Because the raw dye was highly perishable, these textiles must have been produced and dyed near the Mediterranean before they were imported into the Caucasus. This suggests connections between the South Caucasus and surrounding regions, and perhaps the presence of early trade networks.