Dashbulaq

Dashbulaq is one of a series of Medieval sites found in the Shamkir region in northwest Azerbaijan. Additional sites from the same period are located at the Faxrali village in the Goranboy region and at the Lak and Hajiali villages in the Samukh region, also in the northwest. Ganja was one of the largest cities in the Caucasus during the late Middle Ages, before an earthquake in 1139 killed thousands of people. Shamkir was an important fortress on the Shamkir River and the scene of several battles during the early Middle Ages. These various sites provide examples of distinctive, localized examples of medieval society in the area. The remains of historic bridges on the Zayamchai and Shamkirchai Rivers reflect the engineering of the time. Caravans following the greater Silk Road would likely have crossed these bridges as they passed through this portion of Azerbaijan.

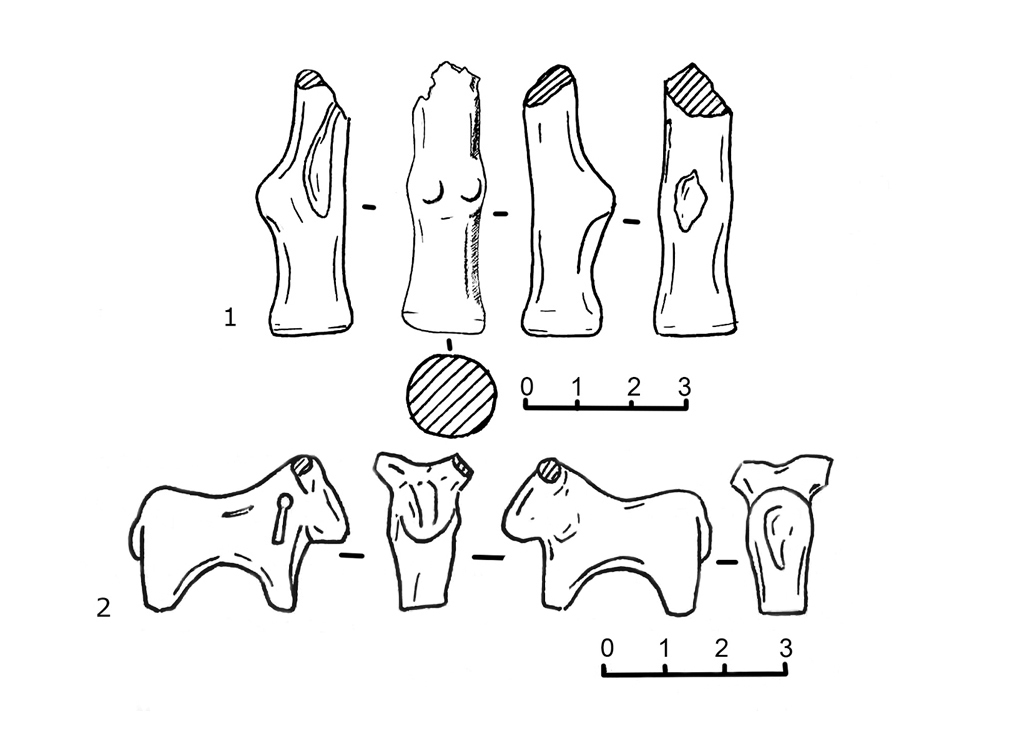

The Dashbulaq site is notable for the number of its archaeological layers, which speak of sequential periods of occupation, destruction, and rebuilding. The village at Dashbulaq was most active between the 9th and 11th centuries AD. Because only a small part of the village site was uncovered excavations took place only where the pipeline route passed directly through the village—it is only possible to speculate about what else might be there. A permanent settlement or town from the period might have contained a bazaar, caravanserai (inn), mosque, and madrasah (school). The excavations at Dashbulaq did, however, reveal numerous features that archaeologists would expect to see in permanent villages and settlements. These features, which also have ethnographic parallels today, include tandirs (clay-formed ovens), massive storage pits, and burial sites. Among the recovered artifacts are typical domestic items such as utilitarian ceramic cooking vessels and finer serving vessels (including a well-preserved stamped pot with an animal motif and glazed pottery in a typical Islamic style). Personal items included fragments of several glass bracelets. The stratigraphy of the material evidence also seems to indicate an initial Christian community followed by a later Islamic one. This transition seems to have occurred at some time in the middle of the 9th century. The pipeline-related excavations found six Christian graves- a relatively small amount of material reflecting this seemingly earlier Christian community at Dashbulaq. However, it is not entirely clear whether these graves belong to the same period.

Hasansu Kurgan

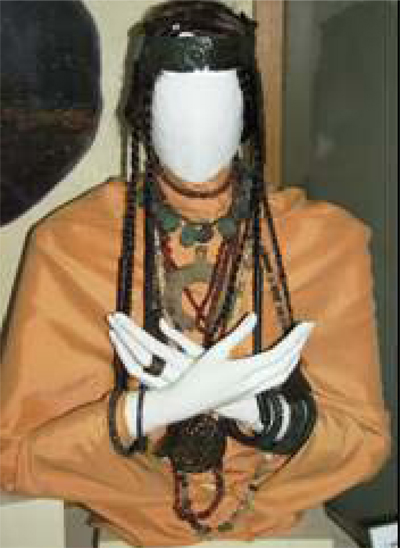

The remains of a kurgan found near Hasansu in western Azerbaijan reflect Middle Bronze Age cultures in the region. The kurgan is similar to those of the Tazakand and Trialeti cultures that spanned Azerbaijan and Georgia from approximately 2,200 to 1,700 BC. It is notable for the fascinating orientation of 71 pottery vessels, adjacent to a deceased juvenile, arranged in distinct parallel lines along two walls inside an excavated kurgan. The shoulders of many of the pots were decorated with etched bands of chevrons and other formal designs. A scattering of domestic animal bones may be from food provided for the deceased in the afterlife. Skulls and leg bones of bulls had been placed in two corners of the burial chamber, a deliberate arrangement perhaps intended to represent a bull-drawn chariot or cart. Other finds included bronze pins, baskets, and perforated beads. Several kurgans excavated at Hasansu are similar to others discovered in the 1980s in the Shamkir region of western Azerbaijan.

The discovery of this kurgan in the AGT Pipelines corridor illustrates the burial practices of the Middle Bronze Age, which had previously been poorly documented in this area. Some archaeologists view the introduction of burials in the style of Hansansu to this region as evidence of foreign populations moving into the region, or of an internal evolution in burial practices.

Zayamchai & Tovuzchai

Multiple graves at Zayamchai and Tovuzchai, two closely related necropoli excavated along the pipeline corridor in Azerbaijan, yielded extensive insights into the burial practices in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (approximately 1,400-700 BC).

In 2002, archaeologists of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography first recorded the Zayamchai necropolis (or “city of the dead”), located on the east banks of the river of the same name, during baseline surveys carried out during Stage 1 of the project. Subsequent excavations conducted in 2003 uncovered over 130 graves that yielded hundreds of intact pottery vessels, many unique bronze artifacts (including daggers, javelin points, and various decorative pieces), and other ritual objects. The findings indicate that advanced Late Bronze Age (Xojali-Gedabey) cultures were present in the Kura Valley at the end of the second millennium BC. The variety and skilled workmanship reflect a highly coherent, structured local society.

The project’s planning team rerouted the pipelines in this area to avoid impacting two other significant cultural heritage sites located nearby. One was a large and complex settlement that seems to date from the Late Bronze Age, and the second was a historic bridge crossing the Zayamchai that likely dates from the Middle Ages.

Tovuzchai

The Tovuzchai necropolis, uncovered on the west bank of the river of the same name, was similar to the necropolis at Zayamchai. The 80- plus graves excavated at this site during 2004 and 2005 similarly revealed a rich burial culture. Particularly noteworthy were the complete pots with the remains of the deceased; in some cases over 20 complete pots had been buried at the same time. Other items from the graves included bronze daggers and arrowheads, bronze bosses (a circular bulge or knoblike form protruding from a surrounding flatter area), and hundreds of beads made from carnelian, agate, and glass paste. The internments at the sites seem to have taken place over several hundred years without notable interruption.

The Tovuzchai graves were of two general types: shallow ones covered by rounded river stones, and deeper earthen ones. There is no clear pattern with respect to grave depth and composition of the items placed in them; some burial chambers were large but modestly furnished, while others were small but filled with rich arrays of burial items. In some, the skeletal remains were disarticulated; in others, the individuals were buried with animals. The head of the skeleton in one grave rested on a number of polished and painted ceramic plates and pots. This arrangement may reflect specific spiritual or religious beliefs. A bronze bracelet, bronze earring, and seashell and agate beads were found on or near the skeleton.

Several large storage vessels found in the nearby village may have been part of the same complex as Tovuzchai necropolis. Archaeological material recovered from the Tovuzchai necropolis indicates that a settlement had existed near this site for six or seven centuries.